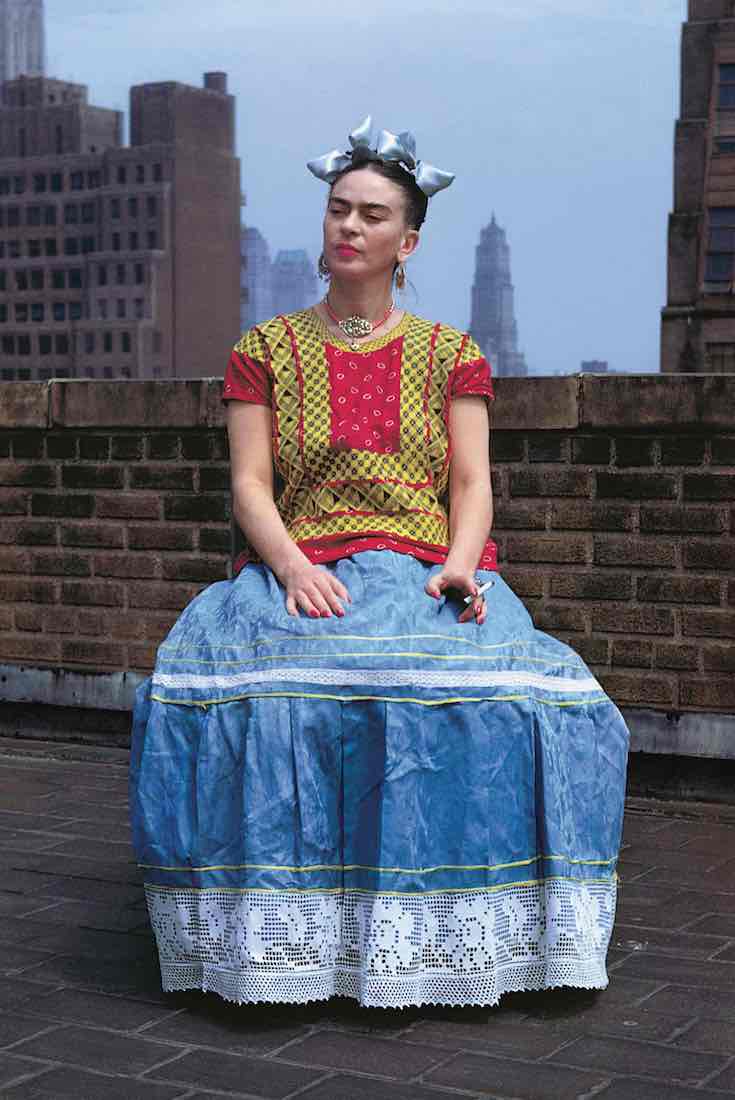

Frida, the unapologetic bitch. Frida, the disabled artist. Frida, symbol of radical feminism. Frida, the victim of Diego. Frida, the chic, gender-fluid, beautiful and monstrous icon. Frida tote bags, Frida keychains, Frida T-shirts, And also, this year’s new Frida Barbie doll (no unibrow). Frida Kahlo has been subject to global scrutiny and commercial exploitation. She has been appropriated by curators, historians, artists, actors, activists, Mexican consulates, museums and Madonna.

Over the years, this avalanche has trivialised Kahlo’s work to fit a shallow “Fridolatry”. And, while some criticism has been able to counter the views that cast her as a naive, infantile, almost involuntary artist, most narratives have continued to position her as a geographically marginal painter: one more developing-world artist waiting to be “discovered”, one more voiceless subject waiting to be “translated”.

In 1938, Frida Kahlo painted Lo que el agua me dio (What the Water Gave Me), the painting perhaps responsible for launching her international career, but also her international mistranslation.